How could neighbors, friends, and loved ones vote for someone whose values I find so offensive to my own, indeed to the very fabric of the United States?

Ill-informed, idiotic, or immoral

I want to address a post to Americans asking these questions about the other half of the voting population today. My comments here are based on my work and teaching experience in business communication and in business and parenting more generally.

In a TED Talk called On Being Wrong, author Kathryn Schultz said the following about people with whom we disagree:

“The first thing we usually do when someone disagrees with us is we just assume they’re ignorant. They don’t have access to the same information that we do, and when we generously share that information with them, they’re going to see the light and come on over to our team.

“When that doesn’t work, when it turns out those people have all the same facts that we do and they still disagree with us, then we move on to a second assumption, which is that they’re idiots. They have all the right pieces of the puzzle, and they are too moronic to put them together correctly.

“And when that doesn’t work, when it turns out that people who disagree with us have all the same facts we do and are actually pretty smart, then we move on to a third assumption: they know the truth, and they are deliberately distorting it for their own malevolent purposes. So this is a catastrophe.”

The Wrong Question

The question of “How could they?” jumps straight to the “They get it and they’re just evil” part of Schulz’s three-part process of experiencing disagreement. But, as the late management guru Peter Drucker said, “The most serious mistakes are not being made as a result of wrong answers. The truly dangerous thing is asking the wrong questions.”

Climb Carefully for Most Rational Decision Making

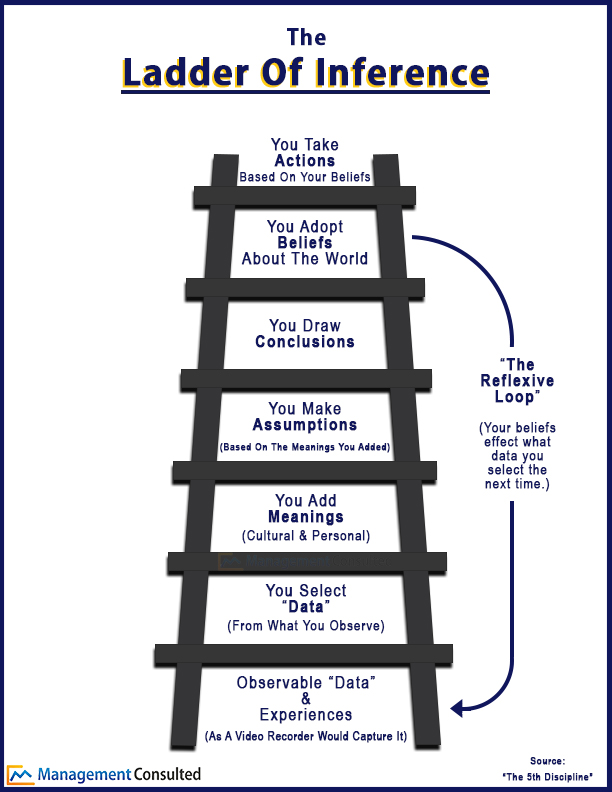

And in this case, “How could they?” is the wrong question. It jumps up the Ladder of Inference irrationally without pausing for self-reflection and critical thinking along the way up. (The ladder’s creator is Chris Argyris, cited on pages 242-246 of Peter Senge’s Fifth Discipline Fieldbook.)

Yes, a small minority of people who disagree with you are simply ill-informed, idiotic, or evil. But – and this is important – most people really aren’t. Most people want the same things we do: safety, security, purpose, and a better life for their children than they had. This is true in all conflicts: Israel-Palestine included.

Humans have more in common than they think they have. Shared humanity has a lot to offer to us when compared with reflexive retreat into ideological corners.

Alternatives

Here are three alternative questions I propose it would be more productive to ask than “How could they?“

- How, if at all, might it benefit me, my party, or my country if I could understand why people really vote differently from how I vote?

- If we assume that a good and moral person were hypothetically to support a candidate whom I strongly oppose, how might that person arrive at that different choice without being ill-informed, stupid, or evil?

- What behaviors of my own would I have to change in order to learn more about the actual reasoning of real people who disagree with me, rather than a caricature I may carry around in my imagination?

By changing our perspective from “ill-informed, idiotic, or immoral” to one of the assumption of shared humanity, I believe we have a tremendous amount to gain individually, as political parties, and as a country.

This post is dedicated to mentor and former colleague Beth O’Sullivan of the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University. She is a living model of these principles at all times — in addition to a teacher par excellence.